As a student pilot, mastering navigation is one of your most crucial skills. You’ll encounter three primary navigation methods during your training: VOR (VHF Omnidirectional Range), GPS (Global Positioning System), and dead reckoning. Each method has its place in aviation, and understanding all three will make you a more competent and confident pilot.

Dead Reckoning: The Foundation of Navigation

Dead reckoning is the oldest form of aerial navigation and forms the backbone of pilot training. Despite its somewhat ominous name, “dead reckoning” simply means navigating by calculating your position based on speed, time, distance, and direction from a known starting point.

How Dead Reckoning Works

The concept is straightforward: if you know where you started, which direction you’re flying, how fast you’re going, and how long you’ve been flying, you can calculate where you should be. The basic formula is:

Distance = Speed × Time

For example, if you’re flying at 120 knots for 30 minutes, you’ve traveled 60 nautical miles in your intended direction.

Tools for Dead Reckoning

- Sectional charts: Your primary navigation tool showing terrain, airports, airspace, and navigation aids

- Plotter: A specialized ruler for measuring distances and plotting courses

- E6B flight computer: For calculating time, speed, distance, and wind corrections

- Watch or timer: Essential for tracking elapsed time

The Dead Reckoning Process

- Plot your course on the sectional chart from departure to destination

- Measure the distance using your plotter

- Calculate heading and groundspeed accounting for wind

- Determine checkpoints along your route (usually every 10-15 miles)

- Calculate time to reach each checkpoint

- Monitor progress during flight and update your position

Advantages and Limitations

Advantages:

- No dependence on electronic equipment

- Develops fundamental navigation skills

- Always available as a backup method

- Improves situational awareness

Limitations:

- Susceptible to cumulative errors

- Requires constant attention and calculation

- Wind changes can throw off calculations

- Less precise over long distances

VOR Navigation: The Radio Beacon System

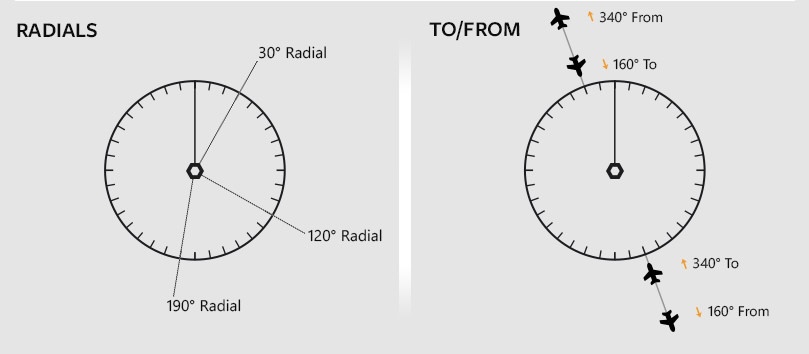

VOR navigation uses ground-based radio stations that transmit signals in all directions. These stations create “radials” – imaginary lines extending outward like spokes on a wheel. VOR has been the backbone of instrument navigation for decades and remains an essential skill for all pilots.

Understanding VOR Basics

Each VOR station transmits on a specific frequency and provides 360 radials, numbered from 001° to 360°. When you tune into a VOR frequency, your aircraft’s VOR indicator shows your position relative to the station.

VOR Equipment

- VOR receiver: Built into most aircraft radios

- OBS (Omnibearing Selector): A knob that selects the desired radial

- CDI (Course Deviation Indicator): A needle that shows your position relative to the selected course

- TO/FROM flag: Indicates whether you’re flying toward or away from the station

How to Use VOR

- Tune the VOR frequency and identify the station with Morse code

- Center the CDI needle by rotating the OBS

- Note the radial you’re on (add 180° to the OBS setting if the FROM flag is showing)

- Track to or from the station by following the CDI needle

VOR Navigation Techniques

Radial Intercept: To intercept a specific radial, set the desired radial on the OBS, note the CDI deflection, and turn toward the needle.

Station Passage: You know you’ve passed over a VOR station when the TO/FROM flag flips and the CDI becomes sensitive.

Cross-Bearing Fix: Use two VOR stations to pinpoint your exact position by finding where two radials intersect.

Advantages and Limitations

Advantages:

- Reliable and time-tested

- Works in most weather conditions

- Provides precise course guidance

- No subscription fees

Limitations:

- Limited range (typically 40-200 nautical miles)

- Line-of-sight limitations at low altitudes

- Requires multiple stations for cross-country flights

- Subject to interference and equipment failure

GPS Navigation: The Modern Standard

GPS has revolutionized aviation navigation, providing precise position information anywhere in the world. Most modern aircraft are equipped with GPS systems, and understanding how to use them effectively is essential for today’s pilots.

How GPS Works

GPS uses a constellation of satellites to determine your exact position through trilateration. By receiving signals from at least four satellites, the GPS receiver calculates your latitude, longitude, altitude, and groundspeed with remarkable accuracy.

GPS Equipment Types

Portable GPS Units:

- Handheld devices like Garmin aviation GPS units

- Tablet apps like ForeFlight or Garmin Pilot

- Great for backup navigation

Panel-Mounted GPS:

- Integrated into the aircraft’s avionics

- More sophisticated features and database updates

- Can drive autopilot and other systems

GPS Navigation Features

Direct-To Navigation: Simply enter your destination, and the GPS provides heading and distance information.

Flight Plan Programming: Create multi-waypoint flight plans with the GPS calculating distances and times.

Moving Map Display: Visual representation of your aircraft’s position relative to terrain, airports, and airspace.

Database Information: Comprehensive airport, navigation aid, and obstacle databases.

GPS Best Practices for Student Pilots

- Always have a backup plan – GPS can fail or lose signal

- Cross-check with other navigation methods – Don’t rely solely on GPS

- Understand your specific GPS unit – Each model has different interfaces

- Keep databases current – Outdated information can be dangerous

- Practice basic GPS operations – Direct-to, flight planning, and nearest functions

Advantages and Limitations

Advantages:

- Extremely accurate positioning

- Worldwide coverage

- Easy to use and program

- Integrated with other avionics systems

- Constant position updates

Limitations:

- Dependent on satellite signals

- Can be jammed or interfered with

- Requires electrical power

- Database updates can be expensive

- May create over-reliance and skill degradation

Integrating All Three Methods

The most competent pilots don’t rely on just one navigation method. Instead, they integrate all three techniques to create a robust navigation system:

The Three-Method Approach

- Plan with dead reckoning – Calculate courses, times, and fuel requirements

- Navigate primarily with GPS – Use for real-time position and course guidance

- Back up with VOR – Verify GPS positions and provide alternate navigation

Practical Integration Tips

Pre-Flight Planning:

- Plot your course using dead reckoning methods

- Identify VOR stations along your route

- Program your GPS with waypoints and alternates

In-Flight Execution:

- Follow your GPS for primary navigation

- Check VOR radials at regular intervals to verify GPS accuracy

- Update your dead reckoning calculations based on actual groundspeed and winds

Emergency Procedures:

- If GPS fails, immediately switch to VOR navigation

- If all electronic navigation fails, rely on dead reckoning and pilotage

- Always maintain situational awareness of your position using all available methods

Common Student Pilot Mistakes

Over-Reliance on GPS: Many student pilots become dependent on GPS and lose fundamental navigation skills. Practice all methods regularly.

Poor Chart Reading: Don’t let electronic displays replace your ability to read and interpret sectional charts.

Ignoring Wind: Dead reckoning calculations are only accurate when wind corrections are properly applied.

Not Verifying Electronic Navigation: Always cross-check GPS and VOR information with visual references when possible.

Inadequate Pre-Flight Planning: Rushing through navigation planning leads to confusion and errors during flight.

Building Your Navigation Skills

As a student pilot, focus on building proficiency in all three navigation methods:

- Master dead reckoning first – It builds fundamental understanding of navigation principles

- Practice VOR procedures – Essential for instrument flying and cross-country flights

- Learn GPS operation – Understand your specific equipment thoroughly

- Integrate methods – Use multiple navigation sources for every flight

- Practice regularly – Navigation skills deteriorate without consistent use

Remember, navigation is both an art and a science. While modern technology makes navigation easier, understanding the fundamentals ensures you can navigate safely regardless of equipment failures or emergencies. Each method has its strengths, and the best pilots know when and how to use each one effectively.

The key to successful navigation isn’t choosing one method over another – it’s understanding how to use all three together to create a comprehensive navigation system that will serve you throughout your flying career.